Art Nouveau Site

History

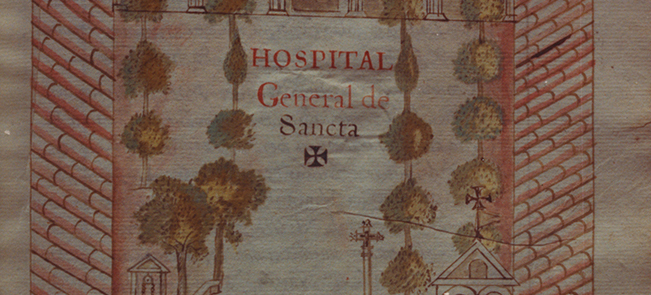

The Mediaeval Hospital

At the start of the fifteenth century, Barcelona had six small hospitals: the Hospital d’en Desvilar (also known as Hospital de l’Almoina); the Hospital d’en Marcús; the Hospital del canonge Colom; the Hospital del canonge Vilar (also known as Hospital de Sant Macià); the Hospital de Santa Eulàlia; and the Hospital de Sant Llàtzer (also known as Hospital de Santa Margarida). All of these institutions were founded by religious orders or individuals, and although under the aegis of the Chapter of the Cathedral and the Consell de Cent, Barcelona’s governing council, almost all of their funds came from the citizens’ charitable donations.

History of the old Hospital de la Santa Creu

Early in 1401, the financial difficulties besetting many of these small hospitals led the Consell de Cent and the Cathedral Chapter to agree to merge these six health centres and construct a single new hospital, thereby improving administrative procedures and the management of resources. This decision was ratified on September 5 of that year by a papal bull of Pope Benedict XIII, approving the establishment of the Hospital de la Santa Creu — the Hospital of the Sant Creu

The new centre, one of the oldest in Europe (and anywhere in the world), was conceived as a large building with four rectangular two-storey wings set around a central courtyard, following the model of an ecclesiastical cloister. King Martin the Humane presided over the laying of the first stone, on 13 February 1401. The work was finally completed in 1450. In due course the building was extended with the construction of the Casa de Convalescència in the seventeenth century, and minor modifications were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Hospital de la Santa Creu was run from its foundation by the Molt Il·lustre Administració (MIA), a body on which two canons and two lay citizens respectively represented the Cathedral Chapter and the Consell de Cent. The income of the institution remained dependent on charitable donations, gifts and bequests from private individuals. This being so, two people, an ecclesiastic and a layman, directly controlled the hospital’s finances.

Over the years, the Hospital’s funding was supplemented thanks to various privileges bestowed by kings and popes, of note among which, by way of example, were the privilege of inheriting the assets of people who die without leaving a will or any legitimate descendant (Alfonso the Magnanimous, 1418) and the ‘privilege of the comedies’ (Philip II, 1587), which granted the Hospital the exclusive right to stage theatrical performances in Barcelona.

The Hospital de la Santa Creu was for more than five centuries the great hospital of the city of Barcelona and its influence area. The charitable activities of the hospital went beyond the care of the sick, and until the late nineteenth century it also had an important role in taking in and training orphaned children.

The Hospital de la Santa Creu made a crucial contribution to the evolution of medicine. Its medical work led to the founding of the Royal College of Surgery, the origin of the future School of Medicine. In fact, from the nineteenth century the hospital was engaged in the intense scientific and educational activity that established its reputation as a medical centre of the first order, on a par with the great European hospitals being built in those years in major cities all across the continent.

By this time, however, the Gothic building in the Raval was starting to show signs of fatigue. After five centuries of uninterrupted activity, the Hospital de la Santa Creu could no longer keep pace with the growth of the city of Barcelona and the constant advances in medicine. The construction of a new hospital had become an absolute necessity.

The Art Nouveau Hospital

The last years of the Hospital de la Santa Creu coincide with the advent of the great urban transformation of Barcelona: the implementation of the Cerdà Plan and the construction of the Eixample ‘new town’.

It was during this period of Barcelona’s expansion beyond its old city walls that Pau Gil i Serra, a Catalan banker living in Paris, died, in 1896. Gil established in his will that his estate be devoted to building a new hospital in Barcelona, and made it clear that the new centre had to bring together the latest innovations in technology, architecture and medicine, and be dedicated to Saint Paul. The result was the Hospital de Sant Pau.

The agreement between the Board of the Hospital de la Santa Creu and the executors of Pau Gil’s will made possible the construction of this new hospital on a site belonging to the Santa Creu bordering on the districts of Gràcia, Horta, Guinardó and Sant Martí de Provençals. Ultimately, the project was entrusted to Lluís Domènech i Montaner (1850-1923), one of the outstanding figures of Catalan Art Nouveau (Modernisme).

The work of Domènech i Montaner

In drawing up his project, the great architect was inspired by the most modern hospitals in Europe. Embracing the latest thinking on sanitation and hygiene, he designed a hospital organised as a series of separate pavilions, surrounded by gardens and interconnected by a network of underground tunnels. Although Domènech’s original scheme comprised a total of 48 buildings, only 27 were actually constructed, of which just 16 were according to the original Modernista plan.

In essence, Domènech created a square plan articulated by two diagonal axes, one north-south and one east-west, in the form of a cross pattée, the emblem of the old Hospital de la Santa Creu, patently summarizing and symbolizing the history of Barcelona’s hospitals and the allegorical values of the Middle Ages.

An unprecedented art nouveau building in Barcelona

In 1902, work began on the first ten buildings of the new complex, laid out on a different orientation from the urban grid of the Eixample. Each building was assigned to a different medical specialty. The natural lighting, the good ventilation and the restrained elegance of the décor made the new Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau a unique place in the world, a pioneering model hospital which affirmed the importance of open space and sunlight in the treatment of patients.

On the death of the architect, his son, Pere Domènech i Roura, took charge of the completion of the work in its final stage. King Alfonso XIII formally opened the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in January 16th 1930.

Over the years, in addition to being the city’s hospital of reference, Sant Pau has become a prominent landmarkwithin the cultural heritage of Barcelona and Catalonia. It was declared a Historic Artistic Monument in 1978, and was recognised as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997.

With the years, too, the ever greater demand for hospital treatment and the structural wear and tear on the buildings made it increasingly difficult for the Modernista complex to meet the demands placed on it and maintain the quality of care. This made it necessary to consider constructing a new, modern hospital suited to the needs of present-day medical practice. Domènech i Montaner’s superb buildings seemed to have reached the end of their working life.

In the autumn of 2009, Sant Pau’s healthcare activities were transferred to a modern building located in the northern section of the grounds, and the Modernista complex took on a new lease of life. A painstakingly thorough restoration has reaffirmed the value of Domènech i Montaner’s work and established Sant Pau as a major international centre for knowledge and a new cultural landmark.

Tickets

Tickets