ACTIVITIES

Hospital architecture studied by Domènech i Montaner

Thursday, 16 November de 2023 11:00h

Temporary exhibition from November 16, 2023 to February 29, 2024.

The project

In 1901, the Most Illustrious Administration of the Hospital de la Santa Creu and the executors of the estate of Pau Gil i Serra agreed to merge two hospitals within a single complex: the Hospital de Sant Pau, to be built with money bequeathed by Pau Gil; and the Hospital de la Santa Creu, which would move to the new site from its original Gothic home, a building that had come to be considered insalubrious and too small.

The commission fell to Lluís Domènech i Montaner. As well as being a renowned architect by this time, he had completed a major project of a similar nature: the Institut Pere Mata, a psychiatric hospital in Reus (1897-1912).

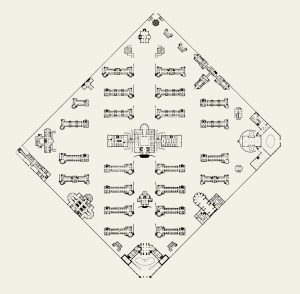

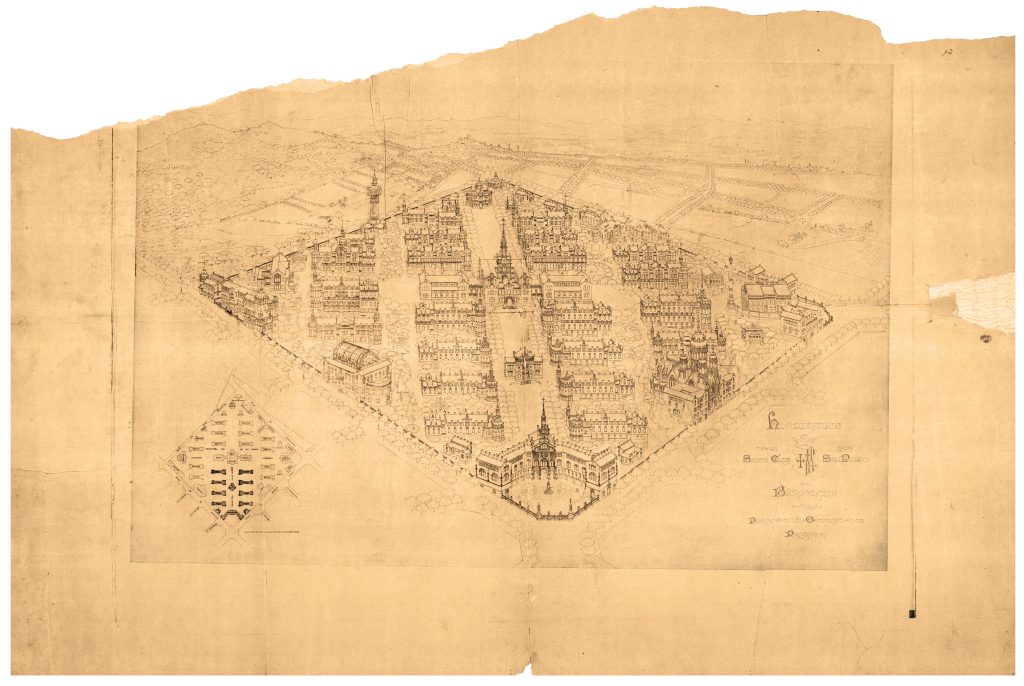

Domènech planned the construction of a large hospital with a capacity for 1,000 patients, consisting of 48 pavilions set in gardens and interconnected by a network of underground service galleries.

His design was never executed in its entirety. There were several reasons for this, the main two being developments in medicine and a lack of funds.

To get an idea of the scale of the project, suffice to say that Domènech submitted a preliminary project in 1902, which allowed work to begin on Sant Pau, but did not deliver the complete project until 1911.

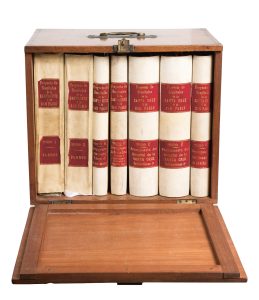

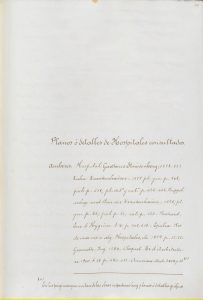

This consisted of seven volumes bound in parchment, presented within a custom-made wooden box, with a clasp and carrying handle. Both the box and the original volumes are kept in the Historical Archive of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau.

Volumes I and II consist of folders containing more than 180 drawings of the project, including floor plans, elevations and cross sections, both of the complex as a whole and of each of its planned 48 pavilions.

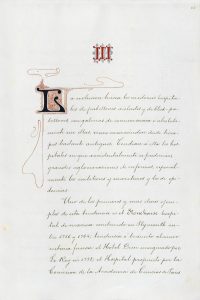

Volume III comprised the architectural programme, report and scope statement.

Volumes IV, V and VI consisted of the breakdown of the budget of the Hospital de la Santa Creu, while that of the Hospital de Sant Pau was set out in volume VII. This was the technical documentation in which costs were listed by item and chapter.

Volume III is the most revealing part of the documentation finally submitted by Domènech, describing not only the ins and outs of the entire project, but also the reason for the design proposed by the architect, in which no decision is left to chance.

The volume comprises three distinct sections. First, we have the Programme, which broadly describes what the characteristics of the hospital complex should be, encompassing everything from the conditions of the site to the necessary facilities. This description is accompanied by a historical overview that includes the latest innovations in hospital design, along with an extensive list of establishments (240) studied for the purpose of the project, located in Europe and other parts of the world.

In the Report, Domènech i Montaner provides a detailed explanation of the project. After reviewing the background to the decision to merge the two hospitals, he gives an extensive description of the plot of land on which the new hospital will be located, of the complex as a whole, and of each of its pavilions. Prominence is also given to the decorative programme.

Lastly, the Scope statement lists the technical terms and conditions for the execution of the works, broken down by article.

The historical overview

In addition to describing the facilities of each pavilion and listing the general conditions of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau complex, Domènech’s programme provides a brief historical overview – including several examples – of the evolution of hospital architecture, explaining how, due to medical developments, hospital complexes consisting of detached pavilions have become the preferred option.

This succinct explanation – amounting to just six pages – allows us to identify the establishments considered crucial by Domènech in the evolution of hospital construction. An analysis of these buildings reveals their many innovative trends and the progress represented by the pavilion-type solution in respect of previous structures. It was considered the most advanced option according to the latest medical developments. Indeed, Domènech begins his explanation by stating that:

“The evolution towards modern hospitals with detached pavilions and block pavilions, with or without connecting galleries, can be traced quite far back in history. The trend was notable in hospitals where large numbers of patients tended to accumulate at certain times, especially military and naval hospitals and those dealing with epidemics.”

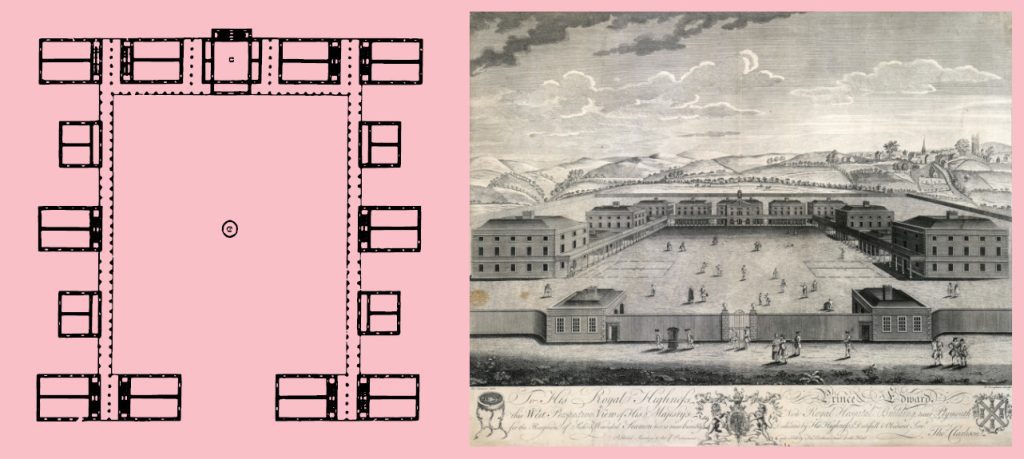

An English precedent

Domènech points out that the existence of pavilion-type hospitals dates back to the 18th century, citing as one of the earliest examples the Royal Naval Hospital at Stonehouse.

Its architect, Alexander Rovehead, aimed to minimise the spread of infection between patients, as well as to ensure good ventilation and natural light. He produced an innovative and highly influential design.

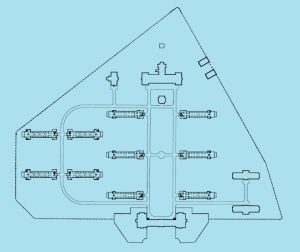

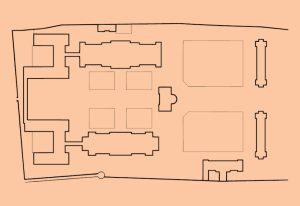

- Royal Naval Hospital, Stonehouse (Plymouth, UK). Alexander Rovehead, 1756-1764

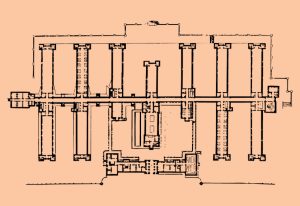

Consolidation and spread of the French model

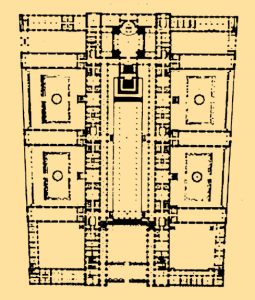

According to Domènech’s account, the pavilion-type hospital system had only recently become established in France. In fact, as early as 1773, Julien-David Le Roy submitted to the Royal Academy of Sciences a project for the rebuilding of the Hôtel-Dieu (city hospital) in Paris, which had burned down a year earlier.

Apart from its larger dimensions, the main novelty that can be distinguished in the Hôtel-Dieu with respect to Stonehouse are the two connecting galleries between pavilions: one at the front, aligned with the courtyard, and one at the rear. Special attention is also paid to the fact that the pavilions, clearly divided into two wings (male and female), are oriented in an east-west direction.

In 1788, the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris published a proposal for a hospital, along the lines of Le Roy’s project, which influenced the planning of this type of establishments until the mid-19th century. In his programme, Domènech gives several examples of designs in France and Belgium that derived from this initial proposal, the latest in chronological order being the Lariboisière Hospital.

This hospital has semi-covered galleries along the courtyard connecting all the rooms. Meanwhile, the patients’ dining rooms are located adjacent to the galleries, between pavilions. Another novelty is the presence of small gardens between the various blocks.

- Project for the Hôtel Dieu (Paris, France). Julien-David Le Roy, 1773

- Project for the la Roquette Hospital (Paris, France). Bernard Poyet, 1787

- Saint-André Hospital (Bordeaux, France). Jean Burguet, 1825-1829

- Saint-Jean Hospital (Brussels, Belgium). Henri Partoes, 1838-1843

- Lariboisière Hospital (Paris, France). Martin-Pierre Gauthier, 1839-1854

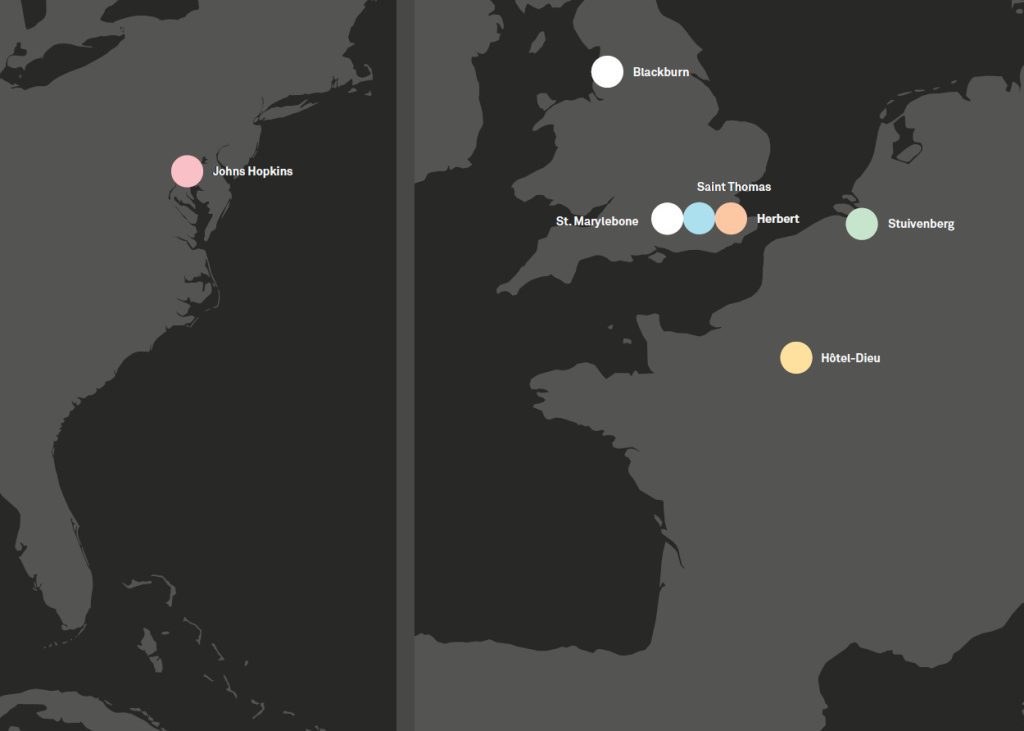

Variations on the French model

Domènech pinpoints the second half of the 19th century as the period in which the pavilion-type hospital structure became fully consolidated.

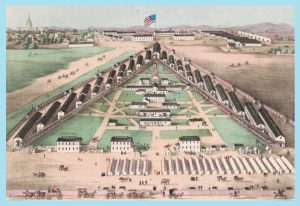

In England, a particular hospital model emerged, with parallel pavilions joined by a single interconnecting longitudinal volume and without the large interior courtyard of the French models. St Thomas’ Hospital and the Herbert Hospital, both located in London, are two examples of this type of structure. Although not explicitly mentioned by Domènech, the popularisation of this model must be attributed to Florence Nightingale, considered the founder of modern nursing, who published her Notes on Nursing in 1852.

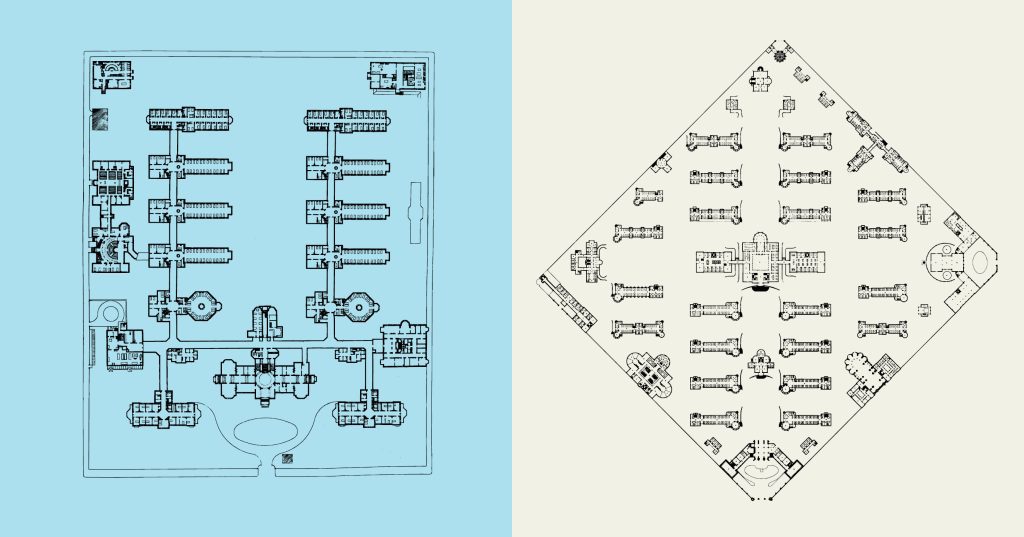

In the United States, the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore merits special attention for its advanced design: a large open garden in which several independent buildings are interconnected by open galleries. Some of the buildings have distinctive façades and independent entrances.

Meanwhile, on the European continent, the French model had become fully consolidated, epitomised by the new Hôtel-Dieu in Paris.

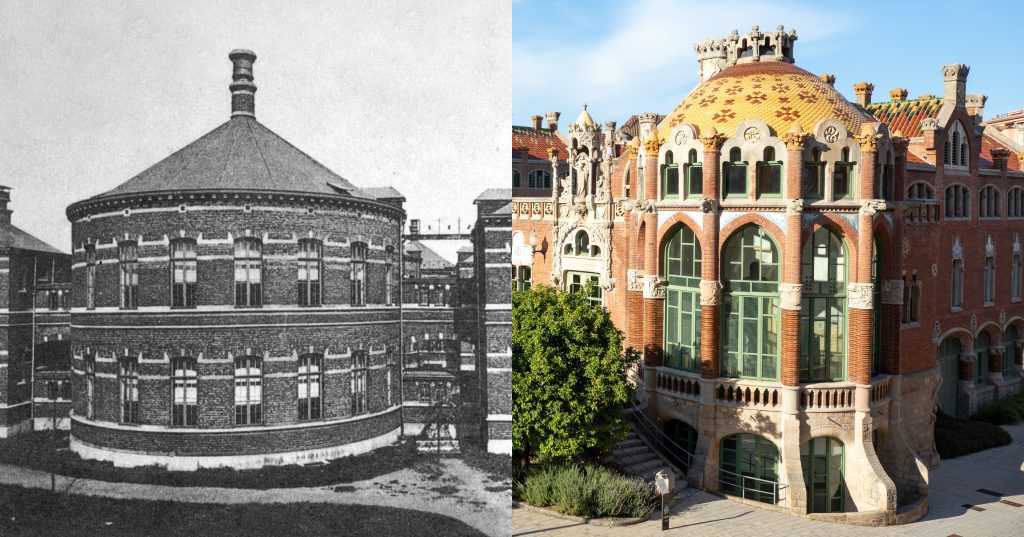

Although it generally matches the French model, the Stuivenberg Hospital in Antwerp also incorporated innovative features, such as the circular shape of the patients’ pavilions, designed to remove angles where bacteria might proliferate, as well as to improve ventilation and lighting.

- St Marylebone Infirmary (London, UK). Jean Burguet, 1825-1829

- Blackburn Royal Infirmary (Blackburn, UK). 1858-1864

- St Thomas’ Hospital (London, UK). Henry Currey, 1866-1871

- Herbert Hospital (London, UK). Douglas Galton, 1865

- Johns Hopkins Hospital (Baltimore, USA). John Rudolph Niernsee, 1876-1889

- New Hôtel-Dieu (Paris, France). Émile Jacques Gilbert, 1866-1876

- Stuivenberg Hospital (Antwerp, Belgium). Frans Baeckelmans, 1877-1884

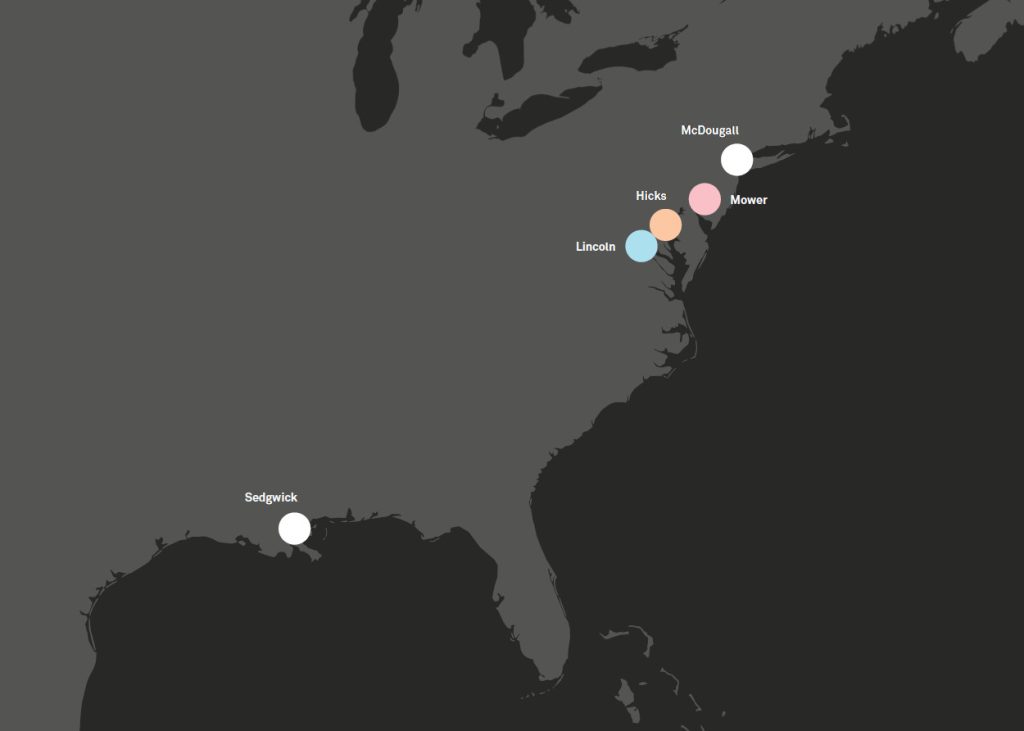

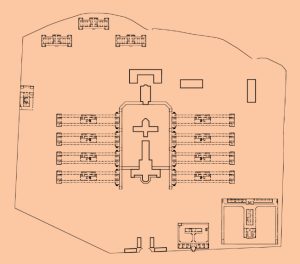

The short-lived hospitals of the American Civil War

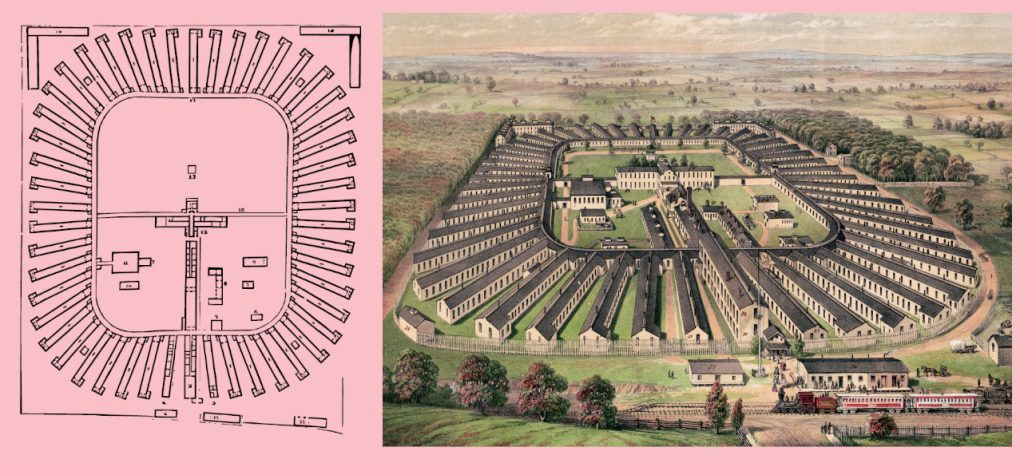

Domènech traces another path of evolution of pavilion-type hospitals: the large military hospitals with interconnected barracks that emerged in modern wars, such as the American Civil War (1861-1865).

These were temporary, single-storey wooden structures built to care for the wounded. They were dismantled after the war. Of the five American Civil War hospitals cited by Domènech, the most notable facility was the Mower General Hospital, built on the outskirts of Philadelphia.

- Mower General Hospital (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). John McArthur Jr., 1862

- Lincoln General Hospital (Capitol Hill, Washington D.C). 1862

- Hicks U.S. General Hospital (Baltimore, Maryland). William Q. Caldwell Jr., 1861

- McDougall Hospital (New York). 1862

- Sedgwick Hospital (New Orleans, Louisiana). 1864

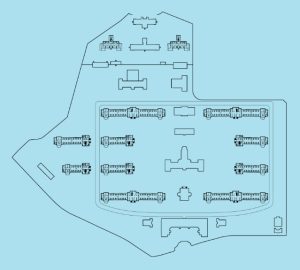

The German detached pavilion model

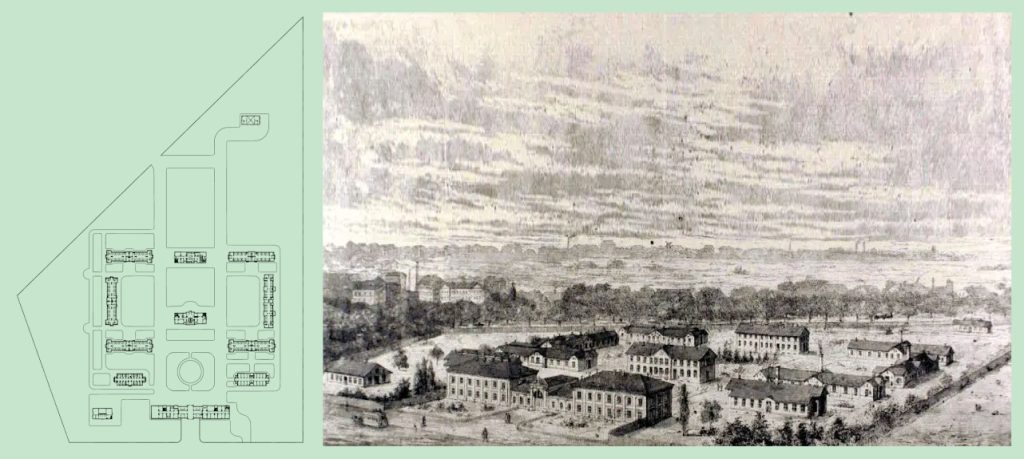

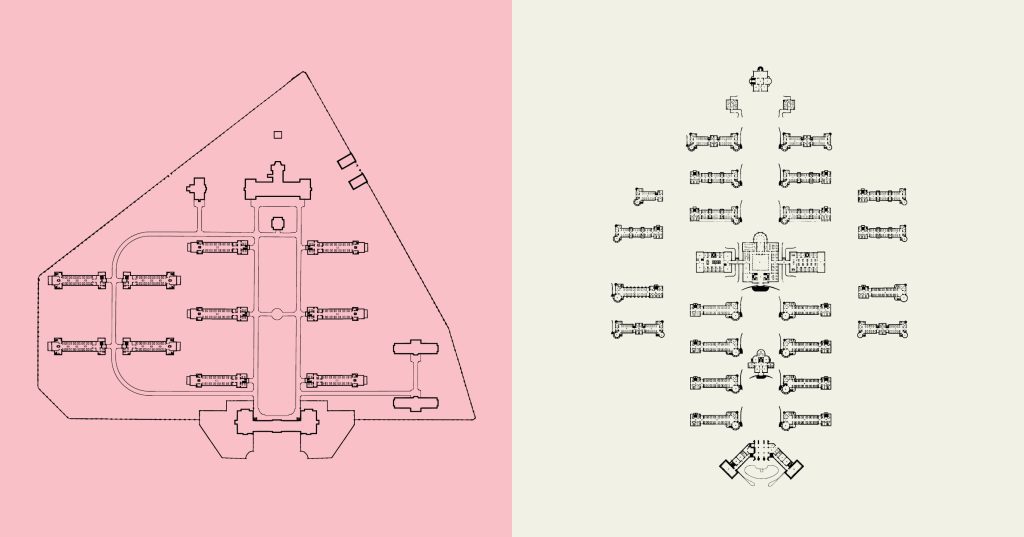

The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) also led to the emergence of a new type of pavilion hospital, in this case in Germany. The novelty here is that the pavilions for patients are fully detached, with no interconnecting gallery. One example is the Tempelhofer Feld military field hospital in Berlin.

From 1870 onwards, the detached pavilion system of field hospitals was fully adopted for permanent hospitals.

In this system, the patients’ pavilions are positioned in parallel, oriented in the same direction, which in this case is not marked by the cardinal points, but rather by the location of the main entrance, which in turn is determined by the urban planning of the site itself.

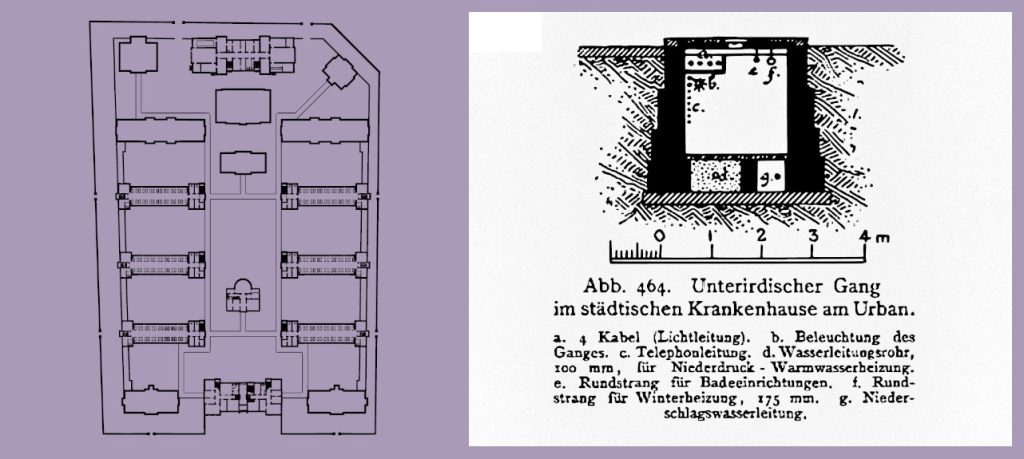

Domènech gives 15 examples of German hospitals that adopt this model, including the Friedrichshain and the Urban in Berlin. The latter is also the first hospital to connect its pavilions with underground galleries, which in this case serve to house water and heating installations.

- St. Jakob Hospital (Leipzig). 1871-1892

- Municipal Hospital (Wiesbaden). 1876-1878

- Carolahaus (Dresden). Theodor Friedrich, 1876-1878

- Eppendorf Hospital (Hamburg). Hans Zimmermann and Friedrich Ruppel, 1884-1889

- Municipal Hospital (Worms). 1885-1888

- Municipal Hospital (Bernburg). 1892-1895

- Municipal Hospital (Nuremberg). Heinrich Wallraff, 1894-1897

- Tempelhofer Feld military field hospital (Berlin). Martin Gropius and Heino Schmieden, 1875

- Friedrichshain Hospital (Berlin). Martin Gropius and Heino Schmieden, 1868-1874

- Kaiserin-Augusta Hospital (Berlin). Hermann Blankenstein, 1869-1870

- Moabit Hospital (Berlin). T. Haese, 1871-1889

- Urban Hospital (Berlin). Hermann Blankenstein, 1887-1890

- Extension of the Charité Hospital (Berlin). 1888

- Kaiser-und-Kaiserin-Friedrich Children’s Hospital (Berlin). 1890

- Robert Koch Institute (Berlin). 1891

The expansion of the detached pavilion model

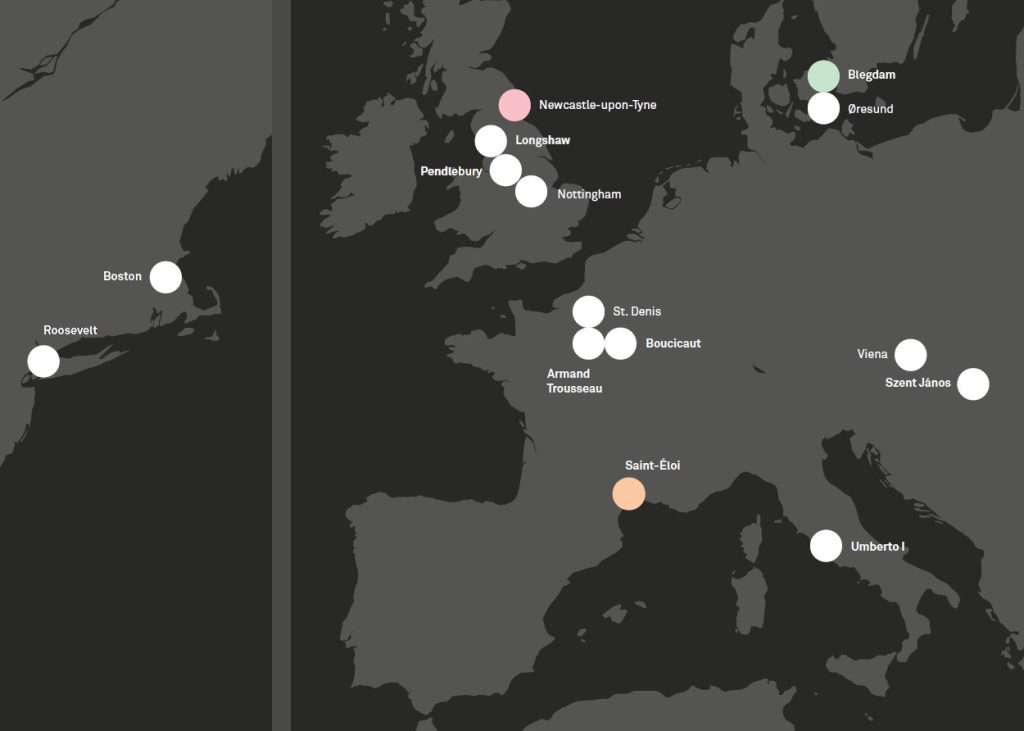

The detached pavilion model that emerged in Germany expanded rapidly. This was because it successfully fulfilled the hygiene-related criteria prevalent at the time, which emphasised the importance of factors such as ventilation and isolation, especially in the case of infectious diseases. In his study, Domènech identifies examples of the expansion of this model in Denmark, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, France, Italy, Great Britain, and even the United States.

In the case of England, he highlights the City Hospital for Infectious Diseases in Newcastle upon Tyne as an example of the establishment of detached pavilions, although the interconnecting galleries typical of English designs in the late 19th century were still present.

In France, the traditional model of the central courtyard was still very important. However, the German system also ended up imposing itself. The Saint Éloi Hospital in Montpellier is a case in point. Initially designed in the French tradition, a group of detached pavilions were added in 1883-1884 for the treatment of infectious diseases.

- Roosevelt Hospital (New York, USA). Carl Pfeiffer, 1869-1871

- Free Hospital for Women (Boston, USA). George Shaw and Henry Hunnewell, 1895

- Øresund Hospital (Copenhagen, Denmark). Vilhelm Friederichsen, 1875-1876

- Blegdam Hospital (Copenhagen, Denmark). Vilhelm Friederichsen, 1878-1880

- Pendlebury Children’s Hospital (Manchester, UK). Nathan Pennington and Thomas Bridgen, 1872-1878

- City Hospital for Infectious Diseases (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK). Arthur Gibson, 1884

- Epidemic Hospital (Nottingham, UK). Arthur Brown, 1891

- Longshaw Fever Hospital (Blackburn, UK). J. B. McCallum, 1894

- Municipal Hospital (Saint-Denis, France). 1880-1881

- Saint-Éloi Hospital (Montpellier, France). Casimir Tollet, 1882. Extended 1883-1884

- Armand Trousseau Hospital (Paris, France). Alexandre Maistrasse and Marcel Berger, 1887

- Boucicaut Hospital (Paris, France). Etienne and Louis Legros, 1898

- Epidemic Hospital (Vienna, Austria-Hungary). Michael Fellner, 1872-1873

- Szent János Hospital (Budapest, Austria-Hungary). Elek Barcza, 1898

- Policlinico Umberto I (Rome, Italy). Giulio Podesti, 1888-1894

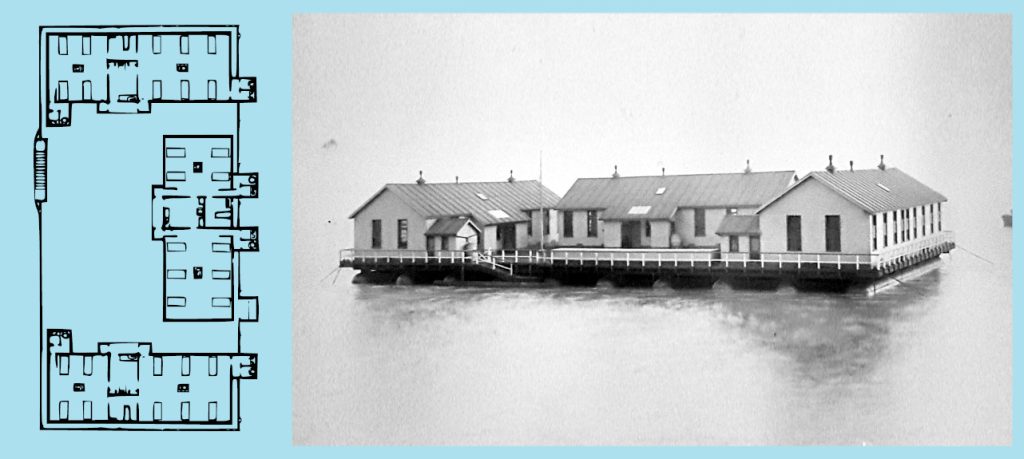

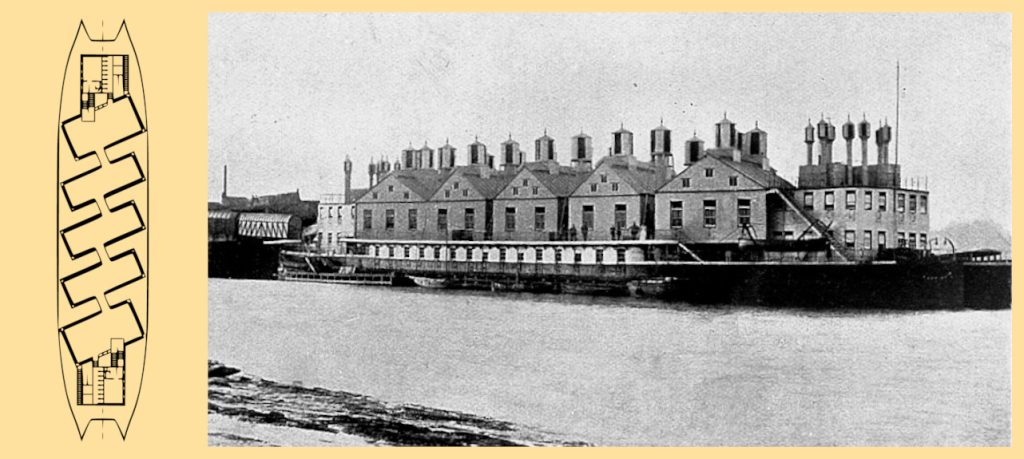

Floating hospitals

In addition to the hospital buildings themselves, Domènech also highlights the innovation represented by the creation of floating hospitals in England, which he considers leading facilities in respect of isolation systems.

These generally consist of large barges permanently docked in rivers, on which independent wooden huts were built for infectious patients.

- Floating Hospital at Jarrow Slake (River Tyne, Jarrow, UK). 1886

- Tees Floating Hospital (River Tees, Middlesbrough, UK), 1895

- PS Castalia Hospital Ship (River Thames, London, UK). 1883

The most modern Spanish establishments

Following the brief review, and as an addition to the general account of the development of modern hospital structures, Domènech devotes a paragraph to various Spanish clinics and hospitals built according to the latest ideas, some of which he visited in person. All of the buildings mentioned have a pavilion-type structure.

Of the examples given by Domènech, the Basurto Hospital in Bilbao is among those whose design is most clearly inspired by German trends. Considered one of the most advanced establishments in Spain, Domènech cites it despite the fact that it was still under construction at the time, showing his awareness of the latest developments in hospital construction.

The Maternity and Orphans House in Barcelona is not strictly a hospital. Moreover, it does not strictly adhere to the typical detached pavilion structure, but rather it consists of a set of block buildings, each of which functions autonomously. Nevertheless, Domènech felt it necessary to mention it in his programme, since it constituted the best local example of the use of rational design in healthcare facilities with the goal of incorporating the latest medical and scientific developments.

- Navy Hospital (Ferrol). Casimir Tollet, 1895-1902

- San Juan de Dios Hospital (Madrid). 1890-1895

- Carabanchel Military Hospital (Madrid). Manuel Cano y León, 1890-1903

- Rubio Institute of Operative Therapy (Madrid). Manuel Martínez Ángel, 1896

- Chamberí Gynaecology Hospital (Madrid). 1901

- Basurto Hospital (Bilbao). Enrique de Epalza, 1898-1908

- Faculty of Medicine Clinics (Zaragoza). Ricardo Magdalena, 1886-1892

- Maternity and Orphans House (Barcelona). Camil Oliveras, 1890-1893

The list of reviewed hospitals

Following the historical overview, Domènech presents a list of all the hospitals reviewed for the purpose of the project, mostly through studying bibliographical material but in some cases by making visits in person. The 30-page list, shown next, includes 240 establishments from all over the world, arranged alphabetically by the city of their location, from Antwerp to Zurich. Each reference includes:

city / establishment / dates of construction / bibliographical references of drawings or images.

Most of the reviewed hospitals are European – 225 – and the rest, except for Cape Town, are located in the United States. The distribution of the hospitals considered leading establishments by Domènech reflected the major centres of scientific, medical and technological innovation of the time. There are no examples from South America, Asia or Oceania, and only one African establishment is listed.

In Europe, three powers are clearly identified: the German Empire, the United Kingdom and France, accounting for 70% of the listed hospitals.

- Netherlands: 1

- Denmark: 2

- Ottoman Empire: 2

- Sweden-Norway: 3

- Switzerland: 3

- Russian Empire: 3

- Italy: 7

- Belgium: 10

- Spain: 12

- United States: 14

- Austro-Hungarian Empire: 16

- France: 47

- United Kingdom (and colonies): 54

- Imperi Alemany: 66

See the complete list of reviewed hospitals by clicking the image:

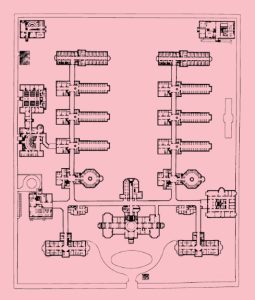

The synthesis

At the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Domènech did not simply adopt a hospital type from among those already consolidated at the time, but rather he studied existing establishments in order to produce the best possible design in every single aspect.

- Detached pavilions

Domènech clearly took the detached pavilion model developed in Germany as his starting point. This system ensures the isolation of patients, which is essential in the case of infections. Friedrichshain Hospital, Berlin

Friedrichshain Hospital, Berlin - East-west orientation

He also shifts the axis of orientation in respect of the surrounding streets, orienting the infirmaries in an east-west direction, as per the French models. This allows more sunlight for patients and natural ventilation. Lariboisière Hospital, Paris

Lariboisière Hospital, Paris - Perimeter spaces

Independent or service pavilions were placed in the perimeter spaces created by the change of orientation. The pavilions had their own street entrances, as was the case in certain American hospitals. In addition to optimising the use of space, this enabled independent access to the hospital facilities without entering into contact with in-patients. Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

Within the general layout, Domènech also incorporates specific elements, adapted from the most innovative hospitals in his review. Some examples are listed below:

- Landscaping

Landscaping of spaces, creating a garden city with therapeutic benefits – as seen in the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

- Underground galleries

Underground galleries connecting pavilions – as seen in the Urban Hospital in Berlin. However, Domènech designs wider galleries to accommodate the circulation of trolleys. To prevent the galleries from being a route for spreading infections, their use was limited to maintenance and “clean” materials.

- Circular spaces

Circular spaces for patients are more hygienic because they prevent the accumulation of dirt in corners – as seen in the Stuivenberg Hospital in Antwerp. This is not a feature of sleeping quarters, but rather of day rooms, where patients spend much of their time.

The originality of Domènech i Montaner’s project lies not so much in his conception of new solutions, but rather in his enormous capacity to incorporate the latest innovations within a consolidated hospital model, creating a coherent complex of great beauty in the form of an almost exuberant Catalan modernism that does not detract from its functionality.

This explains why it is the only hospital in the world to be included in UNESCO’s World Heritage List. It was listed in 1997, when still a fully functioning hospital.

Hospital architecture studied by Domènech i Montaner

Research

Arxiu Històric de l’Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (AHSCP)

Tickets

Tickets