ACTIVITIES

Like an open book:

The historical frieze of Sant Pau Hospital

Thursday, 29 June de 2023 10:00h

Temporary exhibition from June 29 to November 15, 2023.

PRESENTATION

The façade that speaks

The beginnings and subsequent development of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau project were difficult due to the complex institutional relationships that had an impact on the work of Lluís Domènech i Montaner and the project design.

Perhaps this reality, together with the ornamental norms of Modernism, prompted Domènech to include a graphic account of the history of the two hospitals on the façade of the Administration pavilion. These artistic elements tell the story of how the former medieval Hospital de la Santa Creu and the modern one, derived from Pau Gil’s legacy, merged into a single entity to become a reference Hospital in Barcelona.

With this modern “comic”, Domènech left a record of the reality of how the events had unfolded, in addition to producing an exquisite example of the integration of the Arts that would become a part of the History of Architecture.

Lluís Domènech Girbau, Doctor in architecture

Barcelona, March 2023.

Plan of the mosaic frieze with handwritten notes by Domènech i Montaner. (AHSCP)

THE CREATORS

Balance of the parts

Lluís Domènech i Montaner (1850-1923)

Born in Barcelona, he was one of the most important modernist architects. He made notable contributions to society as a historian, politician, and as professor at the Barcelona School of Architecture. In his work he recovered and used a wide variety of applied arts, surrounding himself with great collaborators.

Francesc Labarta i Planas (1883-1963)

Barcelona resident, draftsman, painter and painting teacher. He continued the family tradition, which was also his professional starting point. He studied at the School of Arts and Crafts. Upon finishing his studies in 1904, he came into contact with Lluís Domènech i Montaner, who dissuaded him from the idea of studying architecture. Around the same time, he joined the Sant Pau Hospital team as a draftsman.

Ignacio Alfonso Vicente i Cascante (1886-?)

Born in Zaragoza, he was a draftsman and heraldry specialist. He traced the Gothic letters of the frieze. The importance that Domènech i Montaner placed on heraldry can be seen in the gesture of creating a specialised style of the letters in the frieze.

Mario Maragliano Navone (1864-1944)

Genoese and mosaicist by profession. Son of Giovanni Battista Maragliano, he was also a mosaic builder in Genoa. He was trained at the Italian Ministry of Public Instruction, and in 1884, he settled in Barcelona. The creation of the mosaics of the Comillas Seminary (1889-1892) is one of the first documented collaborations with Lluís Domènech i Montaner.

LLUÍS DOMÈNECH I MONTANER

The idea behind the story

The architect designed the Hospital frieze from the start. He planned it as a functional element that would unite beauty and communication. He specified each one of the spaces where the images would be placed and established all the guidelines for the written text and visual story.

Domènech’s personality indicates that he was a man of the Renaissance, who showed himself to be an inexhaustible source of knowledge in all subjects. In the case of the frieze, we are first captivated by its beauty, then by its functional and pedagogical nature, and finally we discover more hermetic messages, worthy of a universal encyclopaedia.

One can perceive that every detail was studied in depth. Domènech made a synthetic sketch of what he wanted. However, at the same time, he gave full freedom to his collaborators to develop each part of the process, and the confidence that each would add to the balance of the parts.

Lluís Domènech i Montaner. (AHSCP)

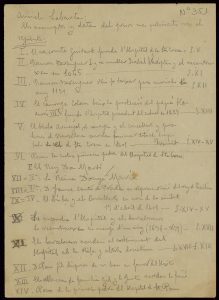

Handwritten note by Domènech i Montaner with the content of the first 14 panels. (AHSCP)

Draft of the main façade, on which the figures of the frieze have already been drawn. (AHSCP)

FRANCESC LABARTA I PLANAS

The transformation of an idea into an image

Throughout his life, Labarta was always an active creator using the decorative arts. He taught at the School of Arts and Crafts in Barcelona, a role that he took on as a result of the work carried out at the Hospital designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner.

He was also a member of several artistic organizations, such as the Sant Jordi Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Barcelona.

Under the pseudonym LATA, he produced drawings of great artistic expression, where the contrast between black and white highlights the figures that appear in his work. Likewise, he played with chromatic spots in the frieze. At the same time, the schematic design of the faces ensures their visibility from afar, although they are blurry when viewed up close. The chromaticism and luminosity of the mosaics remind us of Impressionism.

Labarta passed away at the Hospital de Sant Pau, accompanied by drawings he himself had projected when he was about 20 years old.

Labarta in his study. (BM)

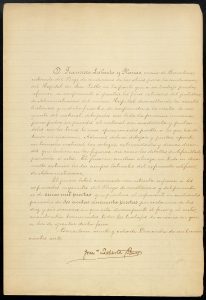

Contract as artist for the mosaics of the Hospital de Sant Pau. (AHSCP)

Singular face by Labarta (Papitu Magazine, circa 1908) and detail from the 7th mosaic.

Detail from Paseo por la playa (J. Sorolla, 1909) and detail from the 7th mosaic.

Drawing for the 7th mosaic divided into sections to adapt it to the architectural scale. (Francesc Labarta / BC)

ALFONSO VICENTE I CASCANTE

The writing

Vicente produced the legends in medieval-style letters at the foot of each image, captions that explain the Hospital’s history. It is a clear example of how every detail was assigned to specialised collaborators. There is not much information about this assistant, although some of his work also appeared in magazines from this period, and it is known that he also participated in the decoration of the grounds of the Poble Espanyol in Montjuïc, a space built for the 1929 Universal Exposition.

In 1956 he published La heráldica general y fuentes de las armas de España [General Heraldry and Sources of the Arms of Spain], a book that reveals his knowledge on the subject, as well as his skill as a draftsman.

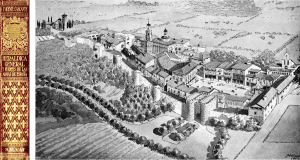

Spine of the book and drawing of Poble Espanyol. (La heráldica general y fuentes de las armas de España. Salvat 1956)

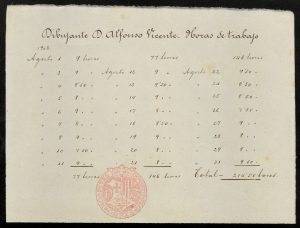

Hours dedicated to the production of the script of the frieze in August 1908, together with the fee. (AHSCP)

MARIO MARAGLIANO NAVONE

The idea transformed into applied art

Maragliano, together with Domènech, renewed the ceramic mosaic craft of Art Nouveau by decorating walls, ceilings and exteriors.

This Italian had different family workshops, the most important of which was on Diputació Street, where he worked to produce the frieze. However, we also know that an on-site workshop was created at Sant Pau to avoid the transfer of the pieces.

The lack of documentation on this artist makes the Hospital de Sant Pau one of the best sources of information about him, as well as a catalogue of some of his works.

As president of the Italians House, a charitable-cultural entity, he accompanied the Italian Queen Elena of Montenegro on her visit to the Hospital de Sant Pau in 1921.

Maragliano died in the hospital surrounded by the mosaics he had created when his name was already recognized in the field of mosaic creation.

Mario Maragliano Navone, 1919. (MHM)

Contract as mosaic art creator. (AHSCP)

Publicity of Mario Maragliano’s workshop. (COAC)

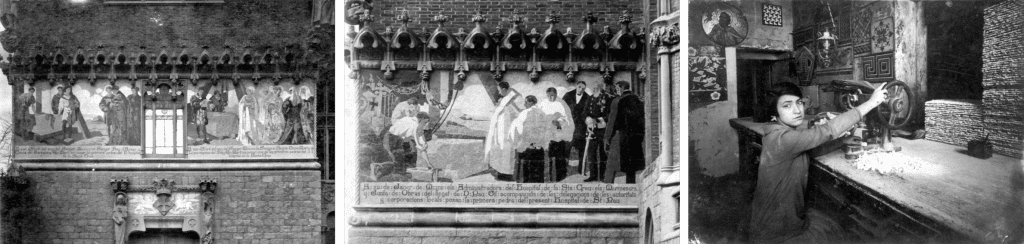

Vintage images of mosaics 6, 7 and 14 (ca. 1911). On the right, Dolors Maragliano i Pagés, youngest daughter of Maragliano, in her father’s workshop. (MHM)

SPACE AND CONSTRUCTION

Graphic narration

The location for the new hospital was an area known as Muntanya Pelada in the Guinardó township. Sparsely populated, the area had only few buildings, primarily farmhouses and a few isolated homes. At an earlier date, the fields had been used to cultivate wine grapes, but the phylloxera parasite (1881) had destroyed the crop. At the time of the hospital’s construction, bushes and scrub were the most abundant vegetation.

The land was property of the Hospital de la Santa Creu, located in the Raval neighbourhood of Barcelona, which had accepted the proposal to incorporate the new hospital (financed with the legacy left by the banker Pau Gil), under the condition that it would be built on land adjacent to the land that had been acquired with the idea of building the future Hospital de la Santa Creu. This is how the project of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau was born.

The executors of Gil’s estate and the architect studied the space and took pictures that show us what it was like and the great transformation it has undergone since that time.

Image taken to verify the condition of the land. Executors of the estate of Pau Gil, 1901. (AHSCP)

Panorama of the upper grounds commissioned by Lluís Domènech i Montaner in 1903. Cyanotypes. (AHSCP)

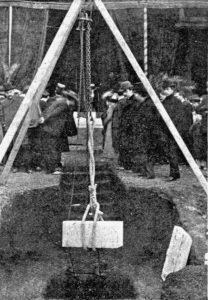

The Administration Pavilion was built between 1905 and 1910. Little by little the building emerged while, at the same time, the frieze was taking shape. It was even finished before the clock tower was crowned.

The Administration Pavilion under construction, with the frieze in the installation phase. (CEC)

Clock tower before its crowning in 1909. (Mercè López Corcoll and Mercè Cantos López / AHSCP)

Cartagena Street (1912). In the background, the Casanovas Hotel is visible. Today it is the Mas Casanovas School. (Josep Salvany / BC)

Façade of the current Pare Claret Street, postcard. (AHSCP)

The completed Administration building, around 1911. (AHSCP)

THE FRIEZE

The most important civilian mosaic of modernism

The frieze of the new hospital (1906-1911) is one of the most relevant representations of the applied arts from the modernist movement. It is the only civilian historiated mosaic produced in that period. It tells of events affecting men and the institution, which, despite its orientation toward well-being and charitable activities, has never been religious.

More than eleven centuries are represented, from the middle of the 9th century to the beginning of the 20th century, and two periods are shown: the medieval era and the modern era.

The entire frieze is a collection of singularities and small representations, a true compositional and technical puzzle. Here, we focus on some details: the facts and characters represented based on historical references from the script written by Domènech; the various sources of inspiration for Labarta to create images similar to those seen in paintings, both reality and imagination, thus creating compositions of great diversity and symbolic richness; and finally, the mosaic technique executed by Maragliano, where we can appreciate his magnificent execution that demonstrates the inherited knowledge of Italian roots used to create an enduring work.

MEDIEVAL ERA

The references to the medieval period include fragments of the hospital’s history from the 9th to the 15th centuries.

The first pages of this book in mosaic show chronicles that depict a period prior to the existence of the institution, taking us back to the history of the independent counts of Barcelona. While the counts were not royalty, they did exercise sovereign power.

The fourth panel documents history of hospital institutions from the year 1219, as the direct antecedents of the creation of the old Hospital de la Santa Creu. The protagonists are kings, nobles and religious representatives, relevant characters all of them, as they were the ones who could act as great benefactors. Their wealth and well-being also depended on the health of their vassals.

The common thread is the creation of the old medieval hospitals of Barcelona.

PRECEDENTS

“In the middle of the 9th century, Guitart, a baron of good memory who is supposed to have been Viscount of Barcelona, founded, under the city walls, the hospital named after Santa Creu and Santa Eulàlia.”

“On the 5th of July in the year of the Lord 1014 [It should be 1045], the count of Barcelona Ramon Berenguer I and his wife Isabel, ordered the restoration of the first hospital under the invocation of Santa Creu and Santa Eulàlia, built under the city walls.”

“In mid-July of the year of the Lord 1131, the count of Barcelona Ramon Berenguer III the Great ordered that he be taken to the Hospital de la Santa Creu to die among the poor.”

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

Viscount Guitart/d is credited with the construction of one of the first documented Catalan urban hospitals. As a confidant of Count Borrell II, he acted as ambassador, so possibly this noble was behind the works.

Count Ramon Berenguer I, known as the Old (1023-1076), stands out for dictating the first Usatges de Barcelona (1068), rules that included reference to the “Principality of Catalonia” in written form for the first time.

His grandson, Ramon Berenguer III, called the Great (1082-1131), stood out due to his leadership in the ongoing struggle against the Muslims. He is referred to as “Guide of the Catalan armies”. He consolidated the power of the count of Barcelona, and shortly before he died, he was ordained knight templar.

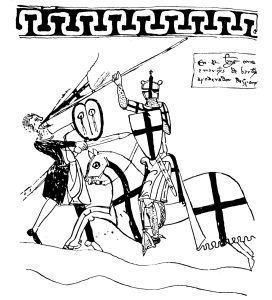

Ramon Berenguer I. Drawing copied by Alfonso Vicente, 1952. (Library of the Monastery of San Lorenzo del Escorial)

Ramon Berenguer III. Genealogical Roll of the Kings of Aragon and Counts of Barcelona, 15th century. (Library of Poblet)

SOURCES OF INSPIRATION

The demolition of the walls during the 18th century, together with the Cerdà Plan, renewed the interest for the evolution and growth of the city. Such topics were reflected in published magazines and lithographs that inspired Labarta.

The second mosaic shows us how the reconstruction of the Guitart/d hospital was located outside the walls. The distance from the city prevented contagions and pandemics. This was the same reasoning that influenced Domènech in the 20th century.

The Plaça Nova with the Roman wall (Postcard, 18th century)

Map showing the Roman wall of Barcelona. (Barcelona histórica, antigua y moderna, 1906)

MOSAIC TECHNIQUE

The tessera is each small piece of hard material such as marble, terra cotta, ceramic or glass cut to size. Their union forms the mosaic.

Glass tesserae of the period. (MEL)

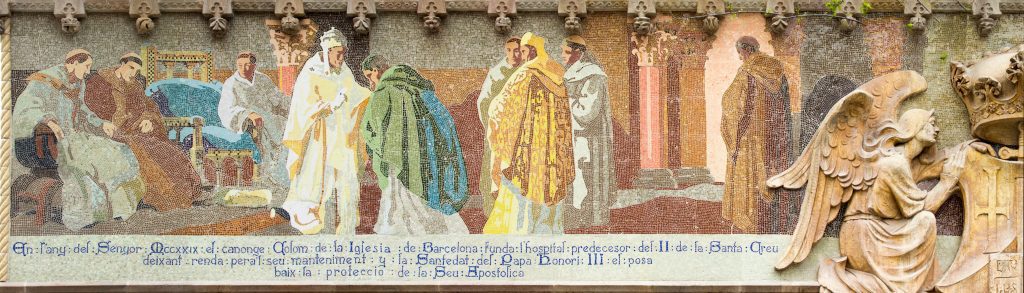

DOCUMENTED PREAMBLE

“In the year of the Lord 1229 [it should be 1219] canon Colom, of the Church of Barcelona, founds the predecessor of the II Hospital de la Santa Creu, leaving means for its maintenance; and His Holiness Pope Honorius III places it under the protection of the Apostolic See.”

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

It presents the foundations for the creation of canon Colom’s Hospital (1219, 13th century), an immediate predecessor of the Hospital de la Santa Creu. It shows characters from the ecclesiastical sphere. Canon Joan Colom (?-1229) was part of the Cathedral chapter and donated different buildings to create the hospital named Colom’s. Pope Honorius III (1148-1227), the 177th of the Catholic Church, promoted the recovery of Holy Land territories in the hands of Muslims.

Pope Honorius III. (Giotto Di Bondone, 1299)

SOURCES OF INSPIRATION

The different religious hierarchies are represented through the costumes. Pope Honorius III and canon Colom stand out in the centre, but we also distinguish members of the mendicant orders approved by this pope: the Franciscans, in dark robes, and the Dominicans, in white.

Dominican friar. (Wenceslaus Hollar, 17th century)

MOSAIC TECHNIQUE

The word “opus” derives from the Latin, and means the way of ordering the tesserae. Broadly speaking, the mosaic of square stones is called “opus tesselatum” and different sequences are created to perfect the drawing.

THE UNION OF MEDIEVAL HOSPITALS

“On the 15th of March 1401, the Council of One Hundred of the city of Barcelona, Bishop Armengol and the canons agree on the merger of the hospitals of Vilar’s, [Desvilar’s,] Marcús’s and Colom’s, to which those of Santa Margarida and Santa Eulàlia were later joined, to constitute the II Hospital de la Santa Creu, with the approval of Pope Benedict XIII.”

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

The Hospital de la Santa Creu was born when different establishments in Barcelona joined to constitute a general hospital. Its construction finished in 1450, and was open for 5 centuries. In 1926, the hospital moved to the new site designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner. Six institutions came together to form it.

Images of the six hospitals that made up the Hospital de la Santa Creu. (Table Book of the Convalescence House, AHSCP)

MOSAIC TECHNIQUE

Ceramic mosaic was he most common in Catalonia at the time. Domènech was the architect that renovated the technique, together with Gaudí and his “trencadís”. Ceramic tesserae only have one coloured side –the glazed side. However, once the mosaic was made, there was not much visual difference, and the mosaic was indigenously produced.

Original ceramics of the time. (MEL)

FIRST STONES OF SANTA CREU

“On the 17th of April in the year of the Lord 1401, the Lord King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona Martin laid the foundation stone of the II Hospital de la Santa Creu.”

“On the 17th of April in the year of the Lord 1401, the Lady Queen Maria de Luna, wife of King Martin, laid one of the foundation stones of the II Hospital de la Santa Creu.”

“On the 17th of April of the year of the Lord 1401, the Infant of Aragon James, Count of Prades, in the name of the Lord King of Sicily Martin, son of the Lord King of Aragon of the same name, laid one of the foundation stones of the II Hospital de la Santa Creu.”

“On the 17th of April of the year of the Lord 1401, the Lord Bishop Joan Armengol and the councillors of the city, the honourable R. Çavall, Ferrer de Marimón, A. Buçot, M. Roure, and L de Gualbes laid one of the foundation stones of the II Hospital of the Santa Creu.”

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

The importance of the foundation is made evident by the presence of royal personages who laid the first stone of the Hospital de la Santa Creu. In a time of terrible epidemics, the creation of a new institution was meant to alleviate the extensive damage caused by the plague.

King Martin I, called the Humane (1356-1410), was king of Aragon, Sicily, and count of Barcelona. Maria de Luna (1353-1406), was his first wife. Native of Aragon, Maria came from the noble house of Luna, and was a relative of Pope Benedict XIII (1328-1423), known as Pope Luna, now considered illegitimate by the Catholic Church. It is recorded that Maria was austere and close to the people, making continual gestures to protect the destitute. They had four children, but the only one who reached adulthood was the aforementioned king Martin of Sicily, called the Younger (1374 -1409), who died before his father Martin the Humane.

King Martin the Humane. Genealogical Roll of the Kings of Aragon and Counts of Barcelona, 15th century. (Library of Poblet)

Maria de Luna. Tomb in the Monastery of Poblet.

King Martin of Sicily the Younger. Genealogical Roll of the Kings of Aragon and Counts of Barcelona, 15th century. (Library of Poblet)

SOURCES OF INSPIRATION

Some figures are inspired by paintings by Jaume Huguet (1412-1492), a representative painter of the Catalan Gothic school. Two reference works were the altarpiece of Saint Abdon and Saint Sennen and that of Saint VCincent. A copy of the latter, signed by Labarta, has been recovered.

Central painting of the Altarpiece of Saint Abdon and Saint Sennen. (Jaume Huguet, 1460)

Saint Vincent ordained by Saint Valerius. Altarpiece of Saint Vincent (Jaume Huguet, 1455-1460) and copy made by Labarta.

MOSAIC TECHNIQUE

Glass was used to define and create some of the mosaic’s most relevant details, such as the faces. It was purchased from workshops in Italy, such as the Orsini House, although it was much more expensive than ceramic tiles.

Glass displays by Angelo Orsini. (MEL)

MODERN ERA

The modern era refers to the institution’s history from the 17th century to the 20th century.

The characters and events are closer to the present and capture the living memory of the city. As the population increased in an industrial city, the number of people affected by illnesses and pandemics also climbed. At the same time, financing was made more challenging with the Confiscation, a Spanish legal norm that led to the loss of financial resources for many Hospitals. Bourgeois families, the emerging economic power, offered new sources of capital.

The second part shows us Pau Gil i Serra (1816-1896), a modern benefactor, who left a sizeable fortune to build a new Hospital for the poor.

The final pages of this book in mosaic show its construction: the Art Nouveau Hospital of Lluís Domènech i Montaner.

THE BURNING AND RECONSTRUCTION OF SANTA CREU

“On the 4th of May in the year of the Lord 1638, the II Hospital de la Santa Creu caught fire. The citizens of Barcelona supported efforts through charity, making it possible to have it completely rebuilt within a year.”

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

It explains the tragic fire of 1638, which shocked the city so much that it was still recorded in many written testimonies many years later. For example, reference to it can be found under the heading “Incendio y saqueo popular” [“fire and popular looting”] in the Memorial Histórico Español published in Madrid in 1888. The text introduces some less altruistic information than that collected by Domènech: “Throngs of people went to the hospital to pillage what they could, despite it being an alms-house.” In the same text, and in subsequent guides, there is an emphasis on the rapid reconstruction thanks to the collaboration of citizens.

Image of the Hospital de la Santa Creu. (Barcelona histórica, antigua y moderna, 1906)

Sick ward of the Hospital de la Santa Creu, 1923. (Jaume Ribera Llopis / AHSCP)

MOSAIC TECHNIQUE

Mosaics were made through the indirect technique. This means that the coloured sides of the tesserae were glued to a production-scale drawing on paper. After that, the wall was prepared with mortar so that the mosaic pieces could be adhered on the plain side. At first, the paper was visible, but once the mortar dried and the tesserae were already attached to the wall, the paper was removed with a sponge and water.

Tesserae on paper. (TM)

FINANCING

“In the 18th and 19th centuries, councillors, aldermen, and citizens of Barcelona provided assistance to the secular Hospital de la Santa Creu by means of numerous legacies and donations, ensured an abundant supply of water, and instituted a raffle draw and other popular fundraisers to secure its ongoing maintenance.”

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

This panel shows the Hospital’s different financing strategies. It depicts the Hospital’s general income management and donation procedures, although the text also makes reference to other systems, from direct charity raised by alms collectors to more participatory approaches that included citizens, such as income from theatrical performances and raffles. There were two kinds raffles, a weekly one in which jewels were raffled off, and an annual raffle, in which participants could win a pig. In relation to theatrical activity, the Hospital enjoyed exclusivity in Barcelona due to a royal privilege granted in 1579.

The Plaça del Teatre on the Rambla and the façade of the Teatre de la Santa Creu, founded in 1560. (Postcard, 19th century)

Image of an alms collector from the. 17th century asking for charity for the Hospital. (AHSCP)

Ticket for the weekly raffle, called “de las alhajas”. (AHSCP)

SOURCES OF INSPIRATION

Although there are few analogies, the general approach of the scene and some figures recall the atmosphere portrayed in the work of Marià Fortuny i Marsal (1838-1874) called La Vicaria, painted in the same period that is represented in this scene.

La Vicaria. (Marià Fortuny, 1870)

THE BENEFACTOR PAU GIL I SERRA

“On the 17th of September 1892, Mr. Pau Gil i Serra, native of Barcelona and resident in Paris, provided in his will for the construction of the present Hospital de Sant Pau.”

“On the 19th of June 1901, through the mediation of Dr. Robert and Mr. Leopold Gil i Llopart, the executors of the legacy of Pau Gil –Mr. Manuel M. Sivatte i Llopart and Mr. Joan Ferrer i Vidal– came to an agreement with the Board of the Hospital de la Santa Creu to jointly undertake the construction of the present hospital.”

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

These two panels show the beginning of the process that led to the creation of the new Hospital de Sant Pau. On the one hand Pau Gil i Serra, businessman and banker of Catalan origin established in Paris, writes a will in which he provides an important legacy for the purchase of land and the construction of a Hospital that will be called Sant Pau. When Pau Gil died (1896), the executors of his will carried out his requests. Once built, the facility would be managed by the Hospital de la Santa Creu.

SOURCES OF INSPIRATION

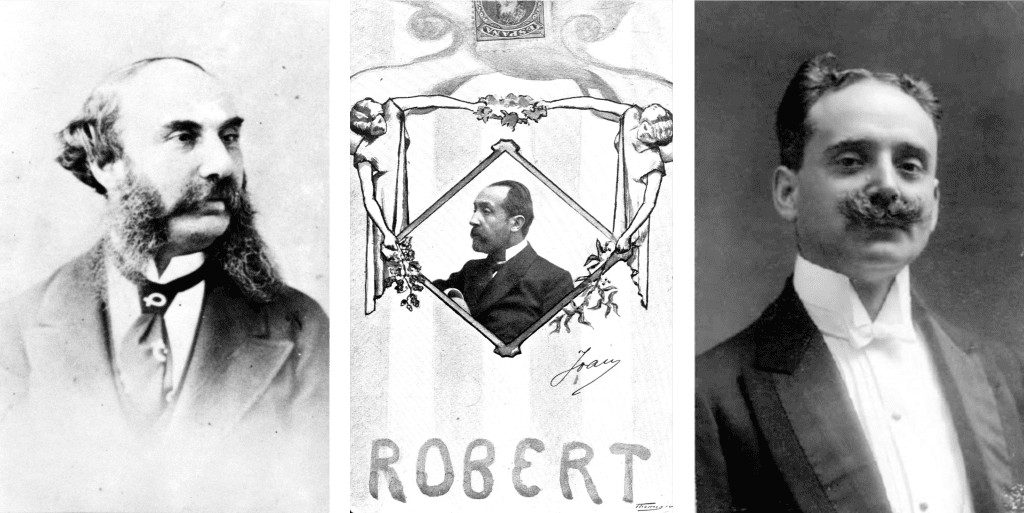

To recreate the place in France where the will was signed, the Panthéon and the coat of arms of Paris appear, indicating the city where Pau Gil resided. Photographs of the characters represented in the scene were most likely used to inspire the artwork. These are Pau Gil himself, as well as the executors of his will, his nephew Leopold Gil Llopart, and Dr. Bartomeu Robert, very influential in Catalonia in the field of health and politics.

Official representation of the coat of arms of Paris.

The Panthéon of Paris. (Lithograph, 19th century)

Portraits of Pau Gil and Serra (left), Dr. Bartomeu Robert (in the centre) and Leopold Gil Llopart (right).

CONSTRUCTION OF SANT PAU

“On the 15th of January 1902, the Administrators of the Hospital de la Santa Creu, the executors and the Works Board of the legacy of Pau Gil, , accompanied by the delegations of local authorities and corporations, laid the foundation stone of the present Hospital de Sant Pau.”

“On Christmas Eve in the year of the Lord 1909, the Holy Cross is set at the top of the building of the present Hospital de Sant Pau.”

SOURCES OF INSPIRATION

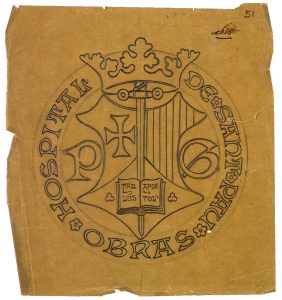

Domènech left the content of the last two panels open, although Labarta’s drawings show us that they were produced at the same time. They represent the contemporary time and the use of the hospital itself as a source of inspiration. They show a large repertoire of details projected by Domènech: the Hospital de Sant Pau coat of arms, the clock tower, and the initial G, from Gil, which is exalted throughout the mosaic, right through the last scenes.

Coat of arms of the Hospital de Sant Pau designed by Domènech i Montaner. (AHSCP)

Current view of the Administration pavilion from Sant Salvador. (Rober Ramos / FHSCSP)

FACTS AND CHARACTERS REPRESENTED

The mosaics show the image of the new building immortalizing the facts present at the time of construction. The clock tower stands out as the most representative element, an icon of Barcelona postcards, and a small tribute to the work and the architect involved in the context of this construction milestone.

Laying of the foundation stone of the Hospital de Sant Pau. (¡Cu-cut! Magazine, 1902)

MOSAIC TECHNIQUE

To make the large mosaic wall panels, the drawing was fragmented into pieces, which fit together like an irregular puzzle in such a way that the fragments are not visible.

In red, the seams where the mosaic pieces fit together. (ÀBAC)

FULL STOP

“On the 11th of March 1923, the Illustrious Bishop of Barcelona Ramon Guillamet laid the foundation stone of the church of this Hospital, in the presence of Illustrious gentlemen Jaume Cararach canon, Carles de Fortuny, Sebastià Puig canon and J. Josep Rocha, as administrators.”

The last page of this mosaic illustrated book shows us an unfinished story. The first stone of the church and the continuation of the works on the medical-sanitary facility of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, which lasted until 1930. From 1923, it was directed by Pere Domènech i Roura (1881-1962), son of Lluís Domènech i Montaner and his right hand.

The modernist complex was in operation until 2009, when the construction of a 21st century hospital was completed within the site perimeter. The hospital’s move to a new headquarters meant closing the pavilions that had remained active for almost a century, making it possible to restore the initial image of the hospital designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997, the largest Art Nouveau ensemble in Europe. This set of mosaics was restored between 2009 and 2011, making it possible to appreciate it in its original splendour.

LIKE AN OPEN BOOK: The historical frieze of Sant Pau Hospital

Research

Marta Saliné i Perich

Coordination

Arxiu Històric de l’Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau

Acknowledgements

Montse Agüero Duran

Elisenda Alonso Sendra

Mario Hernández Maragliano

Silvia Llobet i Font

Images

ÀBAC Conservació-Restauració (ÀBAC)

Arxiu Històric de l’Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (AHSCP)

Biblioteca de Catalunya (BC)

Barcelona Modernista (BM)

Centre Excursionista de Catalunya (CEC)

Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya (COAC)

Fundació Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (FHSCSP)

Museu d’Esplugues de Llobregat (MEL)

Arxiu Mario Hernández Maragliano (MHM)

Taller Mosaicum (TM)

Tickets

Tickets